Building Resilience for the Prevention of Suicide

By Registered Psychotherapist, Patricia James

Sometimes, overwhelming feelings of sadness, hopelessness, worthlessness, and loneliness are enough for some individuals to consider, or attempt to take their own lives. Death by suicide is relatively uncommon but it is estimated that approximately 4,000 people die by suicide each year in Canada (Canadian Psychological Association, 2020). It is more common for individuals to engage in self-harm behaviours and/or entertain suicidal thoughts (CPA, 2020).

In Canada, suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death children/youth age 10 to 19 years and young adults age 20 to 29 years. Although 73% of completed suicide occurs in males between the ages 45 to 59 years, 56% of women in this age category attempt or engage in serious self-harm behaviours resulting in hospitalization (Government of Canada, 2016).

Passive and Active Suicidal Thoughts

Some individuals may have passive suicidal thoughts such as wishing to not wake up or that something fatal will happen. Others have more active thoughts about ending their lives. It is important to take both passive and active suicidal thoughts very seriously because it indicates that something is not right in the individual’s life (CPA, 2020).

Who is most affected by suicidal thoughts/behaviours

Research indicates that suicide is generally more common in people who have mental illnesses such as major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia. Other underlying mental illnesses may include depression, anxiety, or substance misuse disorders. Sometimes chronic pain or physical illness can have a devastating affect for an individual which may also lead to suicidal behaviours (CPA, 2020).

Do people who consider suicide really want to die?

According to the CPA (2020), most people who seriously consider suicide do not want to die. Sources of stress such as personal relationships, social status, school, work or worries about the future can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and pain. If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal ideations or has a plan to attempt suicide, talk to someone about your feelings. There are people who can help you to feel better about life(CPA, 2020).

What should I look out for?

Although depression and suicide go hand in hand, not everyone who dies by suicide is depressed (CPA, 2020). Never the less, if someone is depressed, it is important to find out if they are having suicidal thoughts.

Individuals who are demonstrating behaviours such as:

1. Giving away possessions,

- Have written a suicide note,

- Are talking about self-harm,

- Are gathering items to attempt self-harm/suicide are at risk for suicide.

Individual who have experienced:

1. Recent personal loss,

- Have a history of past attempts are at an even higher risk for suicide (CPA, 2020).

Other signs are:

1. Changes in eating and sleeping habits,

- Withdrawing from others,

- Extreme emotional disturbances,

- Neglect for self-care,

- Loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities.

If you or someone you know is experiencing any of these symptoms or talking about suicide, suicide behaviours or in crisis, it’s important to stay with them and call for help. A suicide and the associated behaviours is a medical emergency (CPA, 2020). Call for help. Call 911 (CPA, 2020).

Mental resilience and how to build it

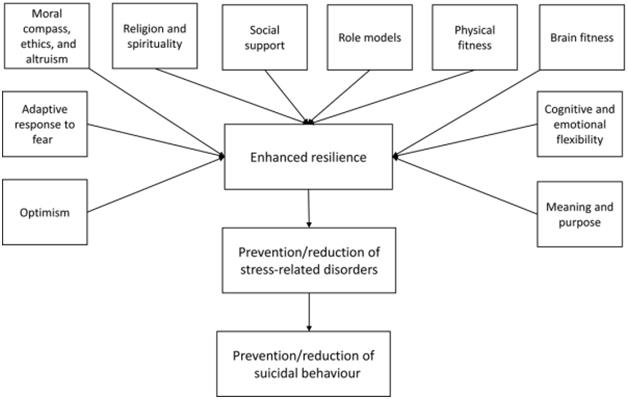

Recent evidence suggests that building resilience may reduce the risk of suicide in at risk individuals. Resilience building for mental health in this day and age seems out of reach for some people (Sher, 2019). We face challenges on a daily basis that erode the foundation of our mental resilience. Care giving needs, finances, health conditions, relationship issues, work-related issues, lock-down restrictions, and a general lack of support build up to cause emotional distress and overwhelm our precious mental resilience reserve. (Poleshuck, Perez‐Diaz, Wittink, et al., 2019). Evidence shows that attaining enhanced mental resilience comes form developing intrinsic motivation which strengthens our ability to cope with life’s challenges in a positive manner. This can be a protective factor against suicide and suicide behaviours (Sher , 2019). Factors depicted below can contribute to mental resilience (Sher, 2019). Of course the question remains.

How do I utilize these factors to build mental resilience?

We can build mental resilience by engaging in healthy lifestyles including:

1. Physical fitness,

- Healthy eating

3. Social activities, - Re-structuring our cognition by replacing negative thoughts/thought patterns for positive thoughts and patterns takes skill and practice but is a key ingredient for enhanced mental resilience (Poleshuck, Perez‐Diaz, Wittink, et al., 2019).

Stress reducing interventions such as:

1.Mindfulness,

2. Meditation,

3. Journaling,

4. Engaging in artful activities are examples of resilience building (Poleshuck, Perez‐Diaz, Wittink, et al., 2019).

- Working with a qualified therapist can help you build mental resilience and allow you to taking control of the chaos and step out of the fog (CPA, 2020).

If you would like more information about Patricia or Brant Mental Health Solutions, call us at 519.302.2300, or email reception@brantmentalhealth.com and book a free 15 minute consultation.

Factors contributing to resilience and the effect of enhanced resilience on stress‐related disorders and suicidal behaviour(Sher, 2019).

Canadian Psychological Association, (2020). Psychology works fact sheet: Suicide. https://cpa.ca/psychology-works-fact-sheet-suicide/

Government of Canada, (2016). Suicide in canada: Infographic. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/suicide-canada-infographic.html

Poleshuck, E., Perez‐Diaz, W., Wittink, M., ReQua, M., Harrington, A., Katz, J., Juskiewicz, I., Stone, J., Bell, E., & Cerulli, C. (2019). Resilience in the midst of chaos: Socioecological model applied to women with depressive symptoms and socioeconomic disadvantage. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(5), 1000–1013. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22188

Sher, L. (2019). Resilience as a focus of suicide research and prevention. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 140(2), 169–180. https://doi-org.roxy.nipissingu.ca/10.1111/acps.13059

Sharon Walker, MSW, RSW

Sharon Walker, MSW, RSW Jordon Iorio Hons. BA, RSW

Jordon Iorio Hons. BA, RSW Christine Bibby, B.S.W., M.S.W., R.S.W.

Christine Bibby, B.S.W., M.S.W., R.S.W. Brianna Kerr, RSW

Brianna Kerr, RSW Danielle Vanderpost, RSW

Danielle Vanderpost, RSW Daniela Switzer, MA, C.PSYCH

Daniela Switzer, MA, C.PSYCH Tammy Adams

Tammy Adams Jade Bates, RMT

Jade Bates, RMT Caitlin Schneider

Caitlin Schneider Dr. Crysana Copland

Dr. Crysana Copland

Amy Dougley

Amy Dougley Emily Kamminga

Emily Kamminga Bill Dungey, RSW

Bill Dungey, RSW

Jessica Moore, RSW

Jessica Moore, RSW Abigail Wragge, RSW

Abigail Wragge, RSW Melanie Clucas

Melanie Clucas Ally Legault

Ally Legault Kunle Ifabiyi

Kunle Ifabiyi Tammy Prince

Tammy Prince